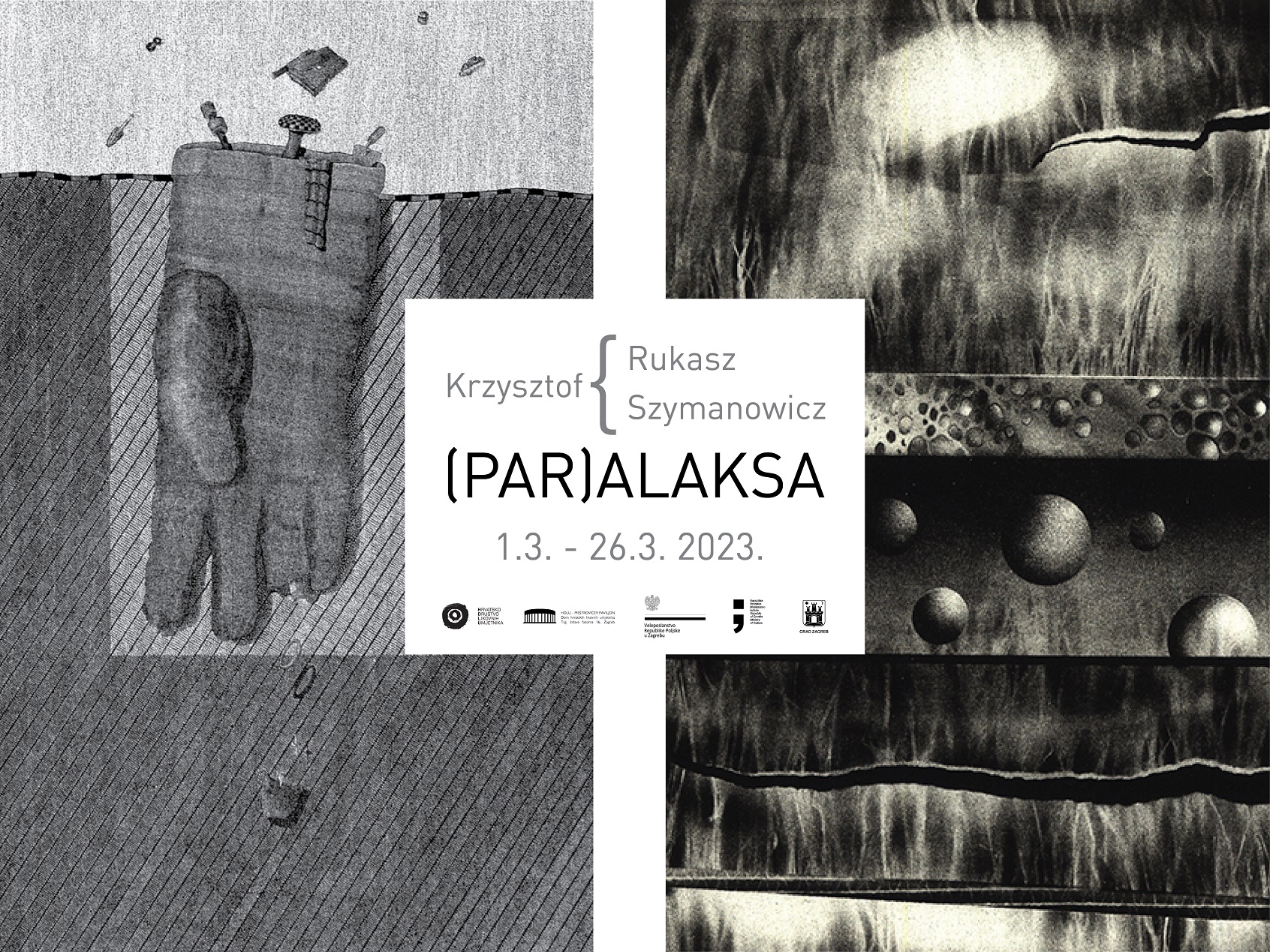

Exhibition: Krzysztof Rukasz & Krzysztof Szymanowicz – (PAR)ALAKSA

Krzysztof Rukasz & Krzysztof Szymanowicz – (PAR)ALAKSA

01. 03. – 26. 03. 2023. u 19.00

Prsten Gallery, Dom HDLU

Exhibition opening: March 1 at 7 pm, 2023

Graphic Double Parallax

It is usually difficult and ungrateful to write about exhibitions of several artists unless there is a solid curatorial concept behind such an exhibition – which, in turn, would make such a job unusually easy. However, with or without a solid concept, when works of art are placed next to each other, we inevitably witness a visual twist that places the viewer in a completely new and unusual situation. Namely, no single interpretation completes the viewing process. Jaques Lacan interprets the openness of the gaze with the counterintuitive principle that the gaze does not belong to us, but that at the same time when looking, we are also passive objects of the gaze that is not ours. In other words, the possibility of constant transformation is not only contained in the different positions of the viewer, but also in the work itself, which persistently eludes a firm interpretation. On the other hand, one should not lose sight of the fact that the context into which the work is placed is also unfinished and that our interpretative framework also carries some unexplored potential. Walter Benjamin best described this relationship in his text “The Task of the Translator“. For Benjamin, translating a text has consequences for both the source and the target language. In translation, the original text is confronted with suppressed meanings, possibilities that were unknowable before being translated. On the other hand, the language of translation reveals all the ways of saying what it was not able to say before. This is how new possibilities are created, translation is not just a mere fraud of the original (traduttore, traditore) but the creation of a new space of meaning – a third space. Although Benjamin spoke about the text, we are faced with a similar situation every time we observe a visual creation. Our field of expectation is faced with a new situation and is looking for anchors by which to establish contact with the work of art. But with the interpretative reaction itself, we supplement our own visual language, transform it, and in doing so, the work also opens up a new possible potential.

In this case, the graphics of two Polish graphic artists, two Krzysztofs – Szymanowicz and Rukasz – enter our space of visual expectation. Both claim that their works have little in common, apart from the fact that they come from Poland, work at the same institution, the Faculty of Fine Arts at Maria Curie-Skłodowska University in Lublin, and that of course they both work in the medium of graphic arts. Krzysztof Rukasz works primarily in the technique of lithography and Krzysztof Szymanowicz in linocut. Krzysztof Szymanowicz was born in Lublin in 1960, where he studied and received his PhD in art from the University of Warsaw. He has had an exceptional career and has won a number of international awards. Krzysztof Rukasz was born in 1968, also in Lublin, and he received his PhD in art in 2007 from Maria Curie-Skłodowska University. He works with innovative ways of combining techniques, for example, he combines lithography and airbrush and promotes his techniques as a guest lecturer at various European universities. Both of them, of course, exhibited at many international exhibitions around the world.

The claim that their approach to the medium of graphics, and even art, is different, is certainly not unfounded, which can be seen even without too much knowledge about their work. Szymanowicz has chosen a path dedicated to understanding memory, remembrance and all that it entails. The questions of why we remember, how we remember and how memory affects our lives are almost fundamental determinants of identification in everyday life. However, memory occurs in fragments, images, tastes, sounds or some hard-to-define atmosphere, and thus remains incomplete, and perhaps even elusive. In the economy of past events, some elements will simply have a greater value, without us being able to understand the play of the past that makes its way into the present. A long time ago, Sigmund Freud described this relationship between something of ours that is also unfamiliar using the term “unheimlich” (uncanny). Later, based on the similar relations of society, language and institutions to the individual, Lacan will offer the concept of extimacy instead of intimacy. By entering the language, our thoughts, dreams and fantasies become tied to a language that is not actually ours but part of the community. Thus, every memory is a kind of shared memory. To tell a personal history, we use language, poetics and discourse that manage fragments. Szymanowicz steals the fragments of this common space and tries to include them in his prints, exploring to what extent the fragments ripped out this way can still possibly provide some other symbolic universe. However, such a transformation finds its expression in the structure, this time in the medium of graphics. And in this very place, Szymanowicz does not try to avoid that new frame within which his fragments will be recorded, quite the opposite. Graphics is a technique that leaves an imprint that opposes the idea of the original. In other words, graphics has no original, only a parallax space of movement. Even memories do not have their originals, they accompany us throughout our lives, we learn to remember those moments with regard to the social and cultural context in which we live. In order to be able to remember at all, the event itself is lost, becoming a matrix for the imprint of the social text. Szymanowicz discovers this connection between memory imprints and graphic matrix in the medium itself. The technique he uses to create the matrix is a dotted, almost pointillistic engraving. Those small incisions, forms without any apparent meaning that will only create a recognizable form in something contextual, are like memory incisions in our consciousness that get their final form only thanks to society.

On the other hand, Rukasz is an artist of search, but not of memory. His search refers to the constant change of both techniques and motives. Rukasz does not pose questions before starting the work, the space in which it moves simply imposes itself as an inexhaustible source for visual questioning. As he claims, ideas for graphics come to him “on their own”. Some of them will be completed in exactly the same form as when he first saw them, and others will undergo a transformation during the process of creation, and some will never be created. Similar to the case of Szymanowicz, there is an imprint of reality in Rukasz’s artistic research as well. At the beginning of his career, Rukasz created his own little universe of a Polish teenager behind the Iron Curtain, for whom a Harley Davidson motorcycle was the object of unfulfilled, and perhaps impossible, desire. However, he soon realized that the development of this idea, which could lead to various research problems, such as social mechanics, youthful illusion, political representation or the concept of freedom, is limiting to his interests. This especially refers to the fear of the interpretative limitation of his work. Running from repetition and accompanying classification, Rukasz devoted himself to creating a personal technique of viewing the world, a kind of reduction. However, it is not a reduction as the one defined by Edmund Husserl in search of a phenomenological method. Rukasz does not try to impose an insight into the true state of the object or provide us with an insight into transcendental consciousness but offers us his subjective reduction – the world as he can see it. That is why, after this shift, his graphics pose a chronological search for the matter from which what he sees is made of. This sequence will lead him to question the very medium of graphics and the question of what is printed and what is not, all the way to dynamic structures, that is, the question of how the flow of time is stopped by graphic means. As is the case with memory, here we are also faced with the problem of imprint, this time the imprint of fragments of the visual field whose origins remain unknown. In a way, Rukasz wants to keep his unknowns, the imprints that will only gain meaning later. In this search, Rukasz is not afraid to make mistakes because he sees his works as constant, unfinished experiments of observation. As with Szymanowicz, the technical performance of the graphics also accompanies Rukasz’s work. His passion for experimentation is reflected in various combinations of techniques, of which the most famous one is certainly lithography combined with the airbrush technique. As he is constantly searching for a visual stimulus, his search also reflects in experimenting with techniques.

Exhibiting these two seemingly different artistic approaches reveals much more in common than one might expect at first glance. The imprints and the questions they pose merely directed the responses of these two artists in different ways. Their graphics show the parallactic nature of artistic work. Parallax is the apparent movement of an object along with the observer’s position. We are most often aware of it when walking on a clear night, and it seems as if the moon is following us. A fundamental philosophical addition to the physical interpretation of parallax was that the object of observation changes along with our position. Translated into the language of theory, the object never exists without the intervention of the subject. In such an approach to parallax or such use of parallax as a theoretical metaphor, there is no world that we only interpret differently according to our own social position or background. The object itself changes its nature in relation to our view. Both artists offer just that, a look into the parallactic nature of time (Szymanowicz) and space (Rukasz). But we still have to open the space of the second parallax, the moment in which their graphics move from the studio in Poland and open to view in the Home of the Croatian Association of Artists. Moving the images will necessarily open up the possibility of changes in the viewer. As is the case with Benjamin’s task of the translator, exhibition visitors can raise the questions that have been in the background, critically observe the positions from which they understand the world around them – experience their parallactic fate of the object observed by the images. In this gap and the need for interpretation, anchoring the visual impulse, it would not hurt to offer something that connects the experience of these artists and our own. The context is of course dynamic and just as limitless, regardless of how much the white walls and silence of the gallery space try to limit it. However, we do not enter the void without previous experiences. Of course, each visitor with their own. But the exhibition is not a moment of individual interpretive matrices, but much more of institutional ones. The birth years of both artists suggest their coming of age in the context of the Cold War division of the world. The short twentieth century in Eastern Europe only revealed the incapability of these societies to create any common narrative about time and space. The time inscribed in the space has been erased, at least the socialist one, but with its erasure, it is as if something else has been erased. This addition to erasure is difficult to clearly identify, it appears as a permanent deficit that deeply determines social division. The history of Eastern Europe is determined by constant geostrategic turbulences in which, for a long time, most of today’s countries have not existed on the political map. Therefore, Eastern Europe is much more a cultural than a geographical term. According to historian Larry Wolff, Eastern Europe was conceptualized (or invented, as the title of his book says) along with the Enlightenment. At the time, the east of the continent became part of a discourse that would be easiest to describe as “almost but not quite” Europe. With its past, firmly inscribed in the general continental one, as if it stopped at a certain point and left the supposedly “natural” course that was happening in the west. Various causes were found for this apparent lack, from the proximity of non-European neighbours to racist theses about the East’s built-in genetic deficiency for progress. The East responded to such imaginations in a wide variety of cultural and political discourses, from attempts to create a “new civilization” to uncritical copying of models and acceptance of inferiority. Whichever side the answer comes from, it has implied the cleansing of history, either from disastrous interventions from the West or from an internal barbaric enemy. What is forgotten is that it is not possible to simply single out influences in society, culture acts as a connected system in an almost chaotic regime, everything is interrelated, and small shifts in some detail result in unpredictable consequences. Deletions and reclassifications thus result in additional losses that are difficult to find and identify.

When we stand in front of the graphics of these two artists, we have to ask ourselves about the ways in which we construct our own visible spectrum and biography, and what is constantly slipping away from them. At the end of the day, we need to think about who owns the space we move through and the memories that define us.

Tomislav Pletenac